A Village Where Murder Became Advice: The Angel Makers of Nagyrév

A Village Where Murder Became Advice

In the early 20th century, the village of Nagyrév sat quietly along the Tisza River, unremarkable and largely forgotten. Long before it became known for the Angel Makers of Nagyrév, life there followed familiar rhythms—meals cooked over open stoves, children raised in crowded homes, illness accepted as part of daily existence. Death was not unusual. People grew sick. Babies didn’t always survive. Old men faded away without question.

That normality is what made the truth so difficult to see.

Behind closed doors, inside dim kitchens warmed by oil lamps and whispered conversations, women began sharing a solution to problems they believed could not be escaped. It wasn’t spoken loudly. It wasn’t written down. It was passed from one woman to another like advice—quiet, practical, and final.

f a husband drank too much.

If an elderly relative became a burden.

If a life felt trapped beyond repair.

There was a way out.

It came in the form of arsenic—clear, tasteless, and nearly impossible to detect. And over time, in Nagyrév, murder stopped being an act of desperation and became something far more disturbing: a shared understanding. What later investigators would call the Angel Makers of Nagyrév did not operate like a cult with sermons or symbols. They were neighbors. Mothers. Wives. And together, they transformed killing into counsel.

Where Nagyrév Was — and Why This Village Mattered

To understand how the Angel Makers of Nagyrév could exist, you have to understand the place itself.

Nagyrév was a small, rural farming village in central Hungary, tucked into the flat lowlands near the winding Tisza River. Like many villages in the region, it was isolated—geographically, economically, and socially. Life revolved around the land, the seasons, and the household. News from the outside world arrived slowly. Authority figures were distant. What happened inside a home was rarely questioned.

This isolation mattered.

In the early 1900s, rural Hungarian villages operated on trust and familiarity rather than oversight. Doctors were scarce. Autopsies were rare. Death certificates were often signed with little investigation, especially when the deceased was elderly, sickly, or an infant. People died at home, not in hospitals. Illness was expected. Grief was routine.

That made Nagyrév the kind of place where something terrible could hide in plain sight.

A culture where suffering was private

Marriage, especially for women, was not easily escaped. Divorce was difficult and socially condemned. Domestic abuse was treated as a private matter, if it was acknowledged at all. Women were expected to endure—emotionally, physically, quietly. When suffering became unbearable, there were few legal or social paths out.

At the same time, large households were common. Aging parents lived with their children. Disabled relatives were cared for at home. Resources were limited. Every extra mouth meant more strain. Resentments could simmer for years behind polite village routines.

War changed everything — and nothing

World War I fractured Nagyrév in ways that were both visible and invisible. Men left the village to fight. Some never returned. Others came back injured, traumatized, or unable to work. Alcoholism increased. Poverty deepened. Traditional family roles shifted, then snapped back into place after the war, often with greater tension than before.

For women, the war brought brief autonomy followed by renewed confinement. For some, it also brought relationships outside their marriages—relationships that became dangerous once husbands returned.

The village survived the war. But it did not come out unchanged.

Why poison fit this world

In a place like Nagyrév, arsenic was the perfect crime.

It was accessible. It could be disguised as illness. It left no obvious wounds. And most importantly, it matched the expectations of death in the village. People expected to get sick. They expected children not to survive. They expected the elderly to fade quietly.

Murder did not arrive as violence.

It arrived disguised as normal life.

This was not a city with police patrols and forensic labs. It was a village where neighbors trusted neighbors—and where advice carried more weight than law.

And in that environment, a secret could spread slowly, patiently, and devastatingly.

The Women of Nagyrév

Before they were defendants in a courtroom or figures in a criminal investigation, the women of Nagyrév were defined by expectations they did not choose.

They were expected to marry young.

They were expected to obey.

They were expected to endure.

For most women in rural Hungary at the turn of the 20th century, life followed a narrow script. Marriage was not simply a personal arrangement—it was an economic necessity and a social obligation. Once married, a woman’s world often shrank to the size of her household. Leaving was rarely an option. Divorce was legally difficult and socially devastating. Abuse, when it occurred, was considered a private matter.

Silence was survival.

Lives built on endurance, not choice

Daily life for women in Nagyrév was physically demanding and emotionally isolating. They cooked, cleaned, raised children, tended animals, and cared for aging relatives—often with little rest and even less autonomy. Illness did not pause responsibilities. Pregnancy did not excuse exhaustion. Poverty sharpened every hardship.

Many women lived under constant strain, trapped between social expectation and personal desperation. There were no shelters. No legal protections. No realistic pathways out of unhappy or violent marriages. When suffering became unbearable, there were few places to turn.

What existed instead was community—tight, insular, and watchful.

Nagyrév was small enough that everyone knew one another’s business, but not close enough to intervene. Advice traveled quietly between women, passed in kitchens, during visits, or while working side by side. These conversations were not dramatic or conspiratorial. They were practical. Grounded in lived experience.

What do you do when there is no escape?

What do you do when endurance feels endless?

Over time, certain solutions began to circulate—not as threats or commands, but as suggestions. As possibilities. As answers to questions that had no acceptable public response.

This is where the story turns darker.

When resentment becomes permission

Resentment alone does not create murder. But resentment combined with isolation, shared grievance, and a lack of consequences can shift moral boundaries.

In Nagyrév, some women began to see death not as violence, but as relief. Not as a crime, but as resolution. The line between survival and wrongdoing blurred slowly, almost imperceptibly.

What mattered most was that these ideas were not born in isolation. They were reinforced through shared understanding. When others around you express the same thoughts—when they validate the same anger and exhaustion—actions that once seemed unthinkable begin to feel reasonable.

This was not madness.

It was normalization.

And once normalized, it only took one trusted voice to show them how.

Auntie Zsuzsi — The Midwife Who Knew Too Much

Every village has someone people trust with their secrets.

In Nagyrév, that person was Zsuzsanna Fazekas.

To the outside world, she was an ordinary rural midwife. To the women of Nagyrév, she was something more. She helped bring children into the world. She tended to the sick. She was present at moments of pain, fear, and vulnerability—moments when people spoke honestly because there was no room left for pretense.

That trust gave her influence. And influence, in an isolated village, carried immense power.

A role built on authority and access

In early 20th-century rural Hungary, a midwife was often the closest thing to a medical professional a village had. Doctors were rare. Hospitals were distant. Midwives were relied upon not just for childbirth, but for advice about illness, women’s bodies, and domestic concerns that could not be discussed publicly.

Women confided in midwives because they had to. They were present at births. They saw the realities of marriage and motherhood up close. They heard whispered complaints that could not be spoken aloud in church or to authorities.

Over time, this placed Fazekas in a unique position—one where knowledge, secrecy, and trust converged.

Help, redefined

At some point, the role of “help” began to shift.

Accounts differ on exactly how it began, but multiple sources agree on the outcome: Fazekas provided women with arsenic and instructions on how to use it. Sometimes she supplied it directly. Other times, she taught women how to extract it themselves. What matters is not the logistics, but the framing.

This was not presented as murder.

It was framed as a solution.

When women came to her overwhelmed, exhausted, or desperate, the answer was not escape or reform. It was removal. A husband who drank too much. A relative who could not be cared for. A situation with no socially acceptable end.

Death was offered as relief—not just for the woman asking, but for the household as a whole.

The danger of trusted voices

What made Fazekas so effective was not coercion. There is no evidence she forced anyone’s hand. Her influence lay in reassurance. In calm explanation. In the way authority normalizes behavior.

When advice comes from someone you trust—someone who has helped you before—it carries weight. Especially when it aligns with thoughts you have already been afraid to name.

Some historians argue that Fazekas was not the sole origin of the poisonings, but rather a central figure in a wider pattern that already existed in the region. Others place her at the heart of the network, the person who transformed scattered ideas into something repeatable.

Both interpretations lead to the same truth: she lowered the threshold.

After that, women no longer had to imagine the unthinkable. They were shown how to do it.

Not a cult — something quieter and more dangerous

The Angel Makers of Nagyrév did not gather for rituals. They did not share doctrine or symbols. There was no initiation, no hierarchy in the traditional sense. What bound them together was not belief, but permission.

Permission to stop enduring.

Permission to stop waiting.

Permission to solve a problem permanently.

Once that permission existed, the act itself became almost procedural. Advice was given. Instructions were shared. The outcome was expected.

And in a village where death already felt ordinary, the extraordinary went unnoticed.

The Poison That Made Murder Invisible

What allowed the Angel Makers of Nagyrév to operate for so long was not secrecy or violence. It was subtlety.

They did not stab or strangle. There were no screams, no blood, no scenes that demanded investigation. Instead, death arrived quietly, disguised as something the village already understood: illness.

Arsenic as an everyday weapon

Arsenic was not a rare or exotic substance in early 20th-century rural Europe. It was commonly found in pest control products, including flypaper, and could be obtained without suspicion. When boiled and processed, it became a nearly colorless, tasteless poison—easy to hide in food or drink.

More importantly, arsenic poisoning mimicked natural disease.

Victims often suffered stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and weakness—symptoms that resembled food poisoning, infection, or chronic illness. In a village where people frequently became sick and medical care was limited, these deaths did not stand out. They fit expectations.

No alarms were raised. No questions were asked.

Why no one noticed

Most people in Nagyrév died at home, not in hospitals. Doctors were rarely present at the moment of death, and autopsies were almost unheard of. If someone had been ill for days or weeks, death was considered a sad but normal outcome.

This meant arsenic left behind no obvious trace.

There were no wounds to examine. No struggle to explain. A grieving family and a signed death certificate were enough to close the matter. Over time, this pattern repeated itself again and again—quiet deaths, familiar symptoms, no suspicion.

Murder blended into routine.

From method to habit

Once women understood that arsenic worked—and that it went undetected—the act itself became procedural. The poison did not need to be administered all at once. It could be given slowly, over time, allowing illness to worsen naturally.

This made killing feel less like an act of violence and more like an intervention. A process. Something managed rather than committed.

The method removed urgency and emotion. It allowed distance.

And in that distance, the moral weight of the act grew easier to carry.

The illusion of mercy

Perhaps the most disturbing part of the poisonings was how they were framed. Arsenic did not only solve problems—it was often seen as merciful. Victims were not beaten or attacked. They faded away.

For women who felt trapped, this mattered.

The poison offered a way to end suffering—sometimes their own, sometimes someone else’s—without confrontation. Without scandal. Without breaking the fragile order of village life.

And because it worked so well, it reinforced itself. Each unnoticed death made the next one easier.

This was how murder stopped looking like murder at all.

When the Deaths Drew Attention

For years, the deaths in Nagyrév blended into the background of village life. People became ill. People died. Funerals followed. Nothing about it seemed unusual—until it began to feel too familiar.

The pattern wasn’t obvious at first. But eventually, the number of deaths became difficult to ignore.

Too many funerals, too few questions

By the late 1920s, deaths in Nagyrév and nearby villages were happening with unsettling frequency. Husbands died. Elderly relatives passed away. Children failed to recover from illnesses that should not have been fatal. In isolation, each death made sense. Together, they formed something harder to explain.

Still, no one spoke openly.

In small villages, suspicion is dangerous. Accusing a neighbor means accusing yourself of knowing too much. It means inviting scrutiny into your own home. Silence had protected everyone for a long time.

Until it didn’t.

The letter that changed everything

What finally broke the silence was not a dramatic confession or a caught-in-the-act moment. It was a letter.

An anonymous message was sent to authorities, accusing women in the region of poisoning their relatives. The letter did not name everyone involved, but it named enough. It described arsenic. It described patterns. It described something officials could no longer dismiss as rumor.

Once the accusation existed on paper, it demanded action.

A secret too large to contain

As investigators questioned villagers, the story grew. Names were added. Connections emerged. What had once felt like individual tragedies began to look like something coordinated, or at least shared.

The advice that had once been whispered in kitchens now echoed in interrogation rooms.

For Nagyrév, there was no returning to normal. The village’s greatest protection—its silence—had collapsed. And once it did, the full scope of what had happened could no longer be denied.

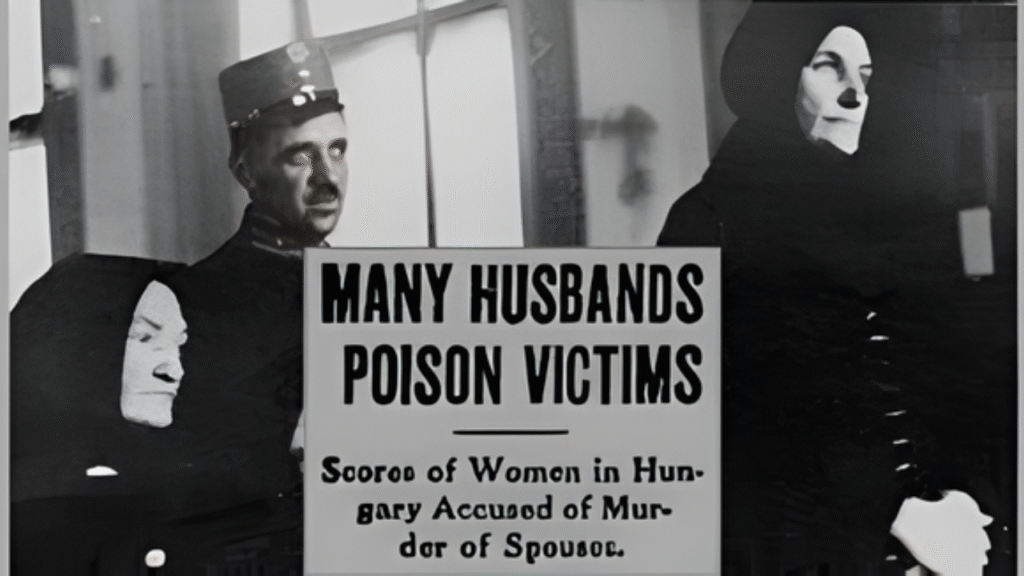

The Trials and the Women Who Stood Accused

Once the investigation began, the quiet isolation that had protected Nagyrév for years disappeared almost overnight.

Authorities did not arrest a single suspect. They arrested many.

Women who had lived side by side for decades—who had cooked together, raised children together, and whispered advice to one another—now found themselves questioned, charged, and brought before the courts. What had once been private became public, and the village was forced to confront what had been happening behind closed doors.

*This article contains affiliate links. You’ll be able to read my full disclosure here.

From rumors to courtrooms

The trials that followed were sprawling and deeply unsettling. Testimony revealed patterns that could no longer be dismissed as coincidence. Women described illnesses that followed the same course. Investigators connected deaths that had never been linked before.

Some defendants confessed. Others denied everything. Some claimed they had only followed advice. Others insisted they had acted out of desperation, not malice.

There was no single narrative—only a web of stories that painted a grim picture of how normalized the poisonings had become.

How many victims were there?

Even during the trials, authorities struggled to answer the most haunting question: how many people had actually died?

Official counts confirmed dozens of poisonings, but estimates ranged much higher. Some investigators believed the number of victims could be in the hundreds, spread across Nagyrév and neighboring villages. Records were incomplete. Many bodies were never exhumed. Countless deaths had already been accepted as natural long before arsenic testing was even considered.

This uncertainty only deepened the horror. The full scope of the killings may never be known.

Justice, punishment, and limits

Several women were convicted and sentenced, including death sentences in some cases, though not all were carried out. Others received prison terms. Many more were investigated but never charged.

What the trials ultimately revealed was not just criminal behavior, but the limits of the justice system itself. By the time authorities intervened, much of the evidence had already faded into the past—buried with the dead.

Nagyrév was left with convictions, unanswered questions, and a legacy it could not escape.

For readers who want a deeper, carefully researched account of the women involved and the trials that followed, I recommend the book Mudlark The Angel Makers: The True Story of the Most Astonishing Murder Ring by Patti McCracken, she offers a detailed examination of the case and its wider social context.

The Body Count Problem — Truth vs. Legend

Even after the trials ended, one question continued to haunt Nagyrév:

How many people actually died?

The official court cases confirmed dozens of poisonings. Investigators were able to test exhumed bodies and detect arsenic in multiple victims. Those findings alone were enough to prove that the killings were real, organized, and far more widespread than anyone had imagined.

But beyond that, the numbers begin to blur.

The confirmed cases

Court records and investigations tied a specific number of deaths directly to the women who stood trial. These cases were supported by testimony, chemical testing, and in some instances, confessions.

Those confirmed deaths place the number somewhere in the dozens.

That alone makes the Angel Makers of Nagyrév one of the most disturbing murder networks in European history.

The highter estimates

Yet many accounts claim the number may have been far higher—sometimes suggesting that hundreds of people across the region could have been poisoned over the years.

Where did those numbers come from?

Some investigators believed not every grave had been opened. Records were incomplete. Many deaths had already been accepted as natural long before suspicion arose. In rural communities, especially during and after World War I, documentation was not always precise.

It is possible that some poisonings were never discovered.

It is also possible that panic and media attention inflated the estimates.

Why the number matters — and why it doesn’t

The uncertainty has become part of the legend.

When victim counts are unclear, stories grow. Headlines expand. Memory fills in the gaps. Over time, confirmed fact and regional rumor begin to overlap.

But here is what remains undeniable:

Dozens of people were poisoned.

Multiple women were convicted.

Arsenic was found in exhumed bodies.

Even at the lowest confirmed number, the scale is staggering.

The real horror of Nagyrév is not whether the number was fifty or two hundred. It is that killing became normalized long enough for dozens of deaths to pass without question.

And that alone is enough.

Was This Really a Cult — or Something Else?

Over time, the Angel Makers of Nagyrév have often been described as a “cult.”

It is an understandable label. The word suggests secrecy, shared belief, and coordinated action. It gives shape to something that feels difficult to explain.

But when historians examine what happened in Nagyrév more closely, the word becomes less precise.

There was no formal leader issuing commands.

No rituals.

No doctrine.

No spiritual ideology guiding the killings.

What existed instead was something quieter—and perhaps more unsettling.

Not belief, but permission

Cults are usually bound by shared ideology. The women of Nagyrév were bound by shared circumstance.

They did not gather to worship or pledge loyalty. They gathered to survive daily life. They shared complaints. They exchanged advice. Over time, that advice shifted from endurance to elimination.

The poisonings were not driven by religious prophecy or radical philosophy. They were driven by normalization.

Once one woman crossed the line and faced no consequences, the boundary shifted for others. The act became less shocking. Less unthinkable. More procedural.

It spread not through doctrine—but through reassurance.

A network built on silence

he Angel Makers did not operate like an organized criminal ring in the modern sense. There was no hierarchy chart. No secret symbol. No coded language.

What they shared was understanding.

In isolated communities, silence can be powerful. If no one speaks, nothing is exposed. If no one reports, nothing is investigated. And when multiple households benefit from that silence, it reinforces itself.

The network existed because people allowed it to.

Why the “cult” label persists

The term “cult” survives because it feels dramatic. It offers a tidy explanation for something chaotic. It allows us to distance ourselves from the reality of what happened.

If it was a cult, then it was abnormal. Extreme. Separate from ordinary society.

But if it was not a cult—if it was instead a community slowly adjusting its moral boundaries under pressure—that is harder to accept.

Because it means the conditions, not just the individuals, mattered.

And conditions can exist anywhere.

When Good People Cross the Line

The story of the Angel Makers of Nagyrév forces an uncomfortable question:

Were these women monsters?

Or were they ordinary people who slowly crossed a line that no longer felt like a line?

History often makes it easy to separate villains from everyone else. But the events in Nagyrév are harder to categorize. These were not outsiders. They were mothers. Wives. Neighbors. Women who attended church and shared meals.

What changed was not their humanity.

What changed was the boundary.

How moral lines move

Psychologists have long studied how people justify behavior that once seemed unthinkable. When an action produces relief instead of punishment, the brain rewrites the rule. What was once shocking becomes practical. What was once forbidden becomes manageable.

If others are doing the same thing, the shift happens faster.

In communities under stress—war, poverty, confinement—those shifts can feel even more rational. Desperation narrows perspective. Survival becomes priority. And slowly, step by step, moral lines adjust.

Not all at once.

Just enough.

Environment matters more than we think

In The Lucifer Effect, psychologist Philip Zimbardo explores how ordinary people can commit harmful acts when shaped by certain environments. His research shows that behavior is often influenced less by personality and more by circumstance, authority, and group pressure.

Nagyrév was not a laboratory experiment. But it was an environment.

An isolated village.

Limited options.

Shared frustration.

Silence that protected everyone involved.

Under those conditions, something shifted.

If you are interested in understanding how environment and group dynamics influence behavior, The Lucifer Effect by Philip Zimbardo offers a deeper exploration of how ordinary individuals can cross moral boundaries under pressure.

The danger of normalization

Perhaps the most unsettling part of this story is not the poison itself. It is how easily the act became advice.

When harm is framed as practical.

When others reassure you it is acceptable.

When consequences do not appear immediately.

The unthinkable becomes routine.

And once routine, it spreads.

The Angel Makers of Nagyrév remind us that evil does not always arrive with banners and speeches. Sometimes it arrives quietly, disguised as relief.

A Village Where Murder Became Advice

The Angel Makers of Nagyrév were not bound by robes, rituals, or prophecy.

They were bound by familiarity.

What makes their story linger is not only the poison, or the trials, or the uncertain number of victims. It is the slow shift that allowed the unthinkable to become ordinary. Advice passed between neighbors. Silence reinforced by shared benefit. A community that adjusted its moral boundaries just enough to survive—until survival turned into something else.

Nagyrév forces us to look at a harder truth about history.

Evil does not always announce itself.

It does not always arrive as fanaticism.

Sometimes it settles in quietly, disguised as practicality.

And when enough people accept it, it stops feeling like a crime at all.

The Angel Makers remind us that the most dangerous transformations are often the quietest ones.

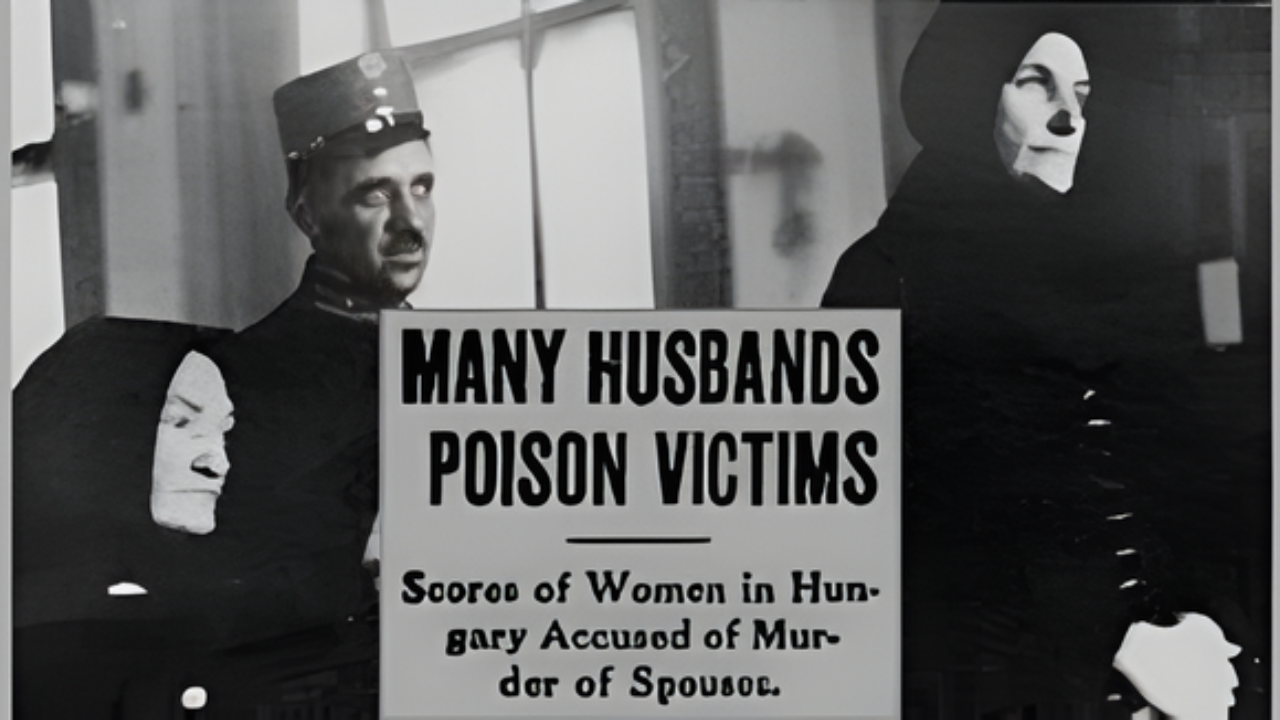

Watch the Full Story: The Angel Makers and Other Deadly Cults

The Angel Makers of Nagyrév are only one part of a larger history of communities shaped by belief, fear, and influence. In the video below, I explore this case alongside other infamous movements—including the Millerites and the movement surrounding Prophet Matthias—examining how shared conviction and social pressure can reshape entire communities.

If you prefer to experience the story visually, you can watch the full breakdown here.